OUR TEAM

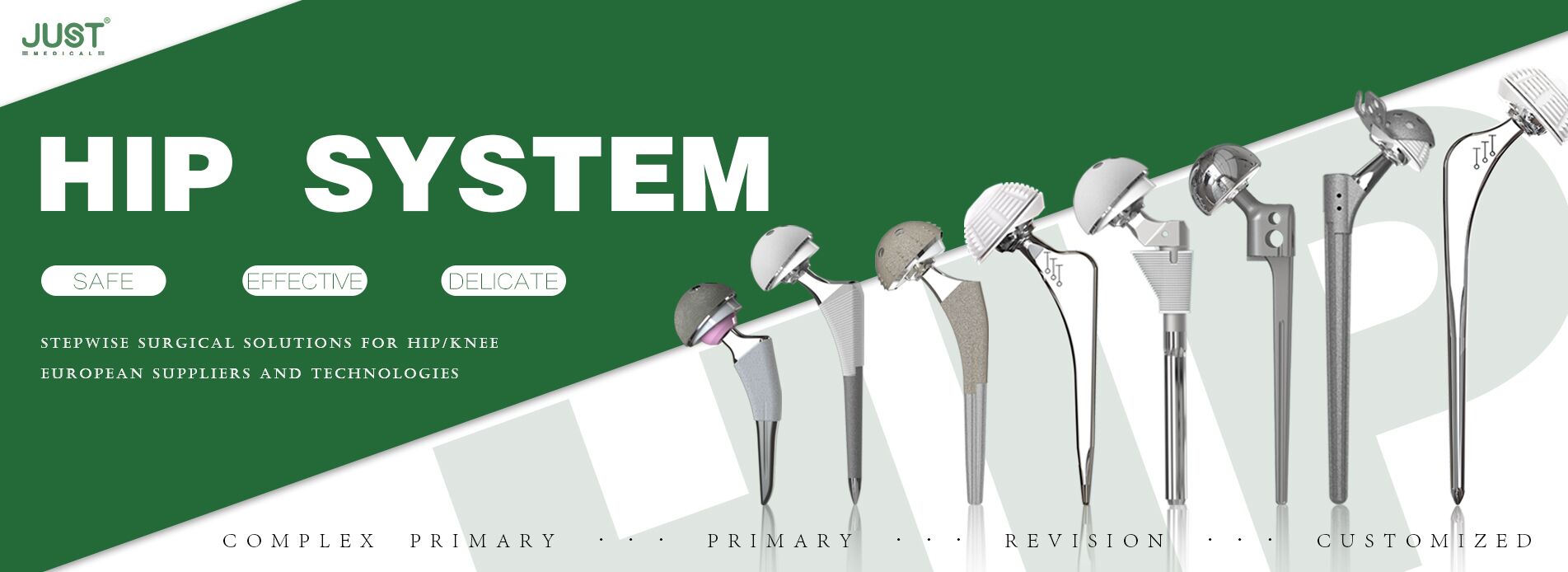

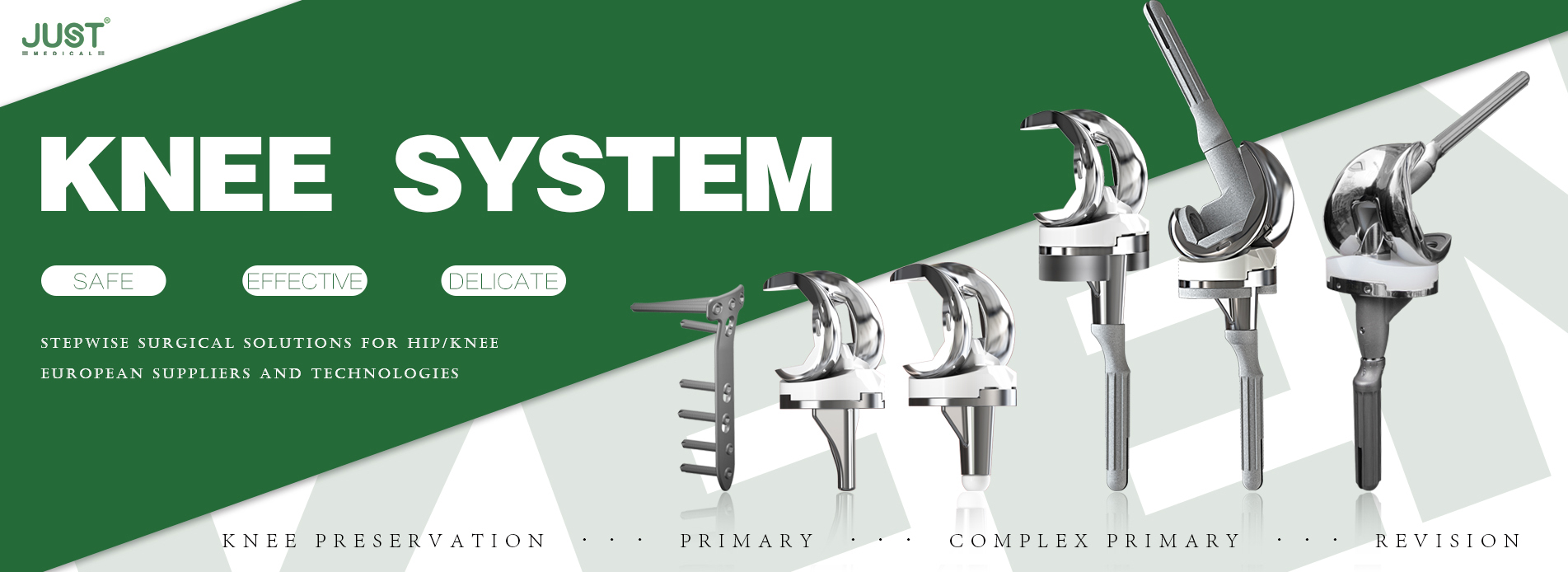

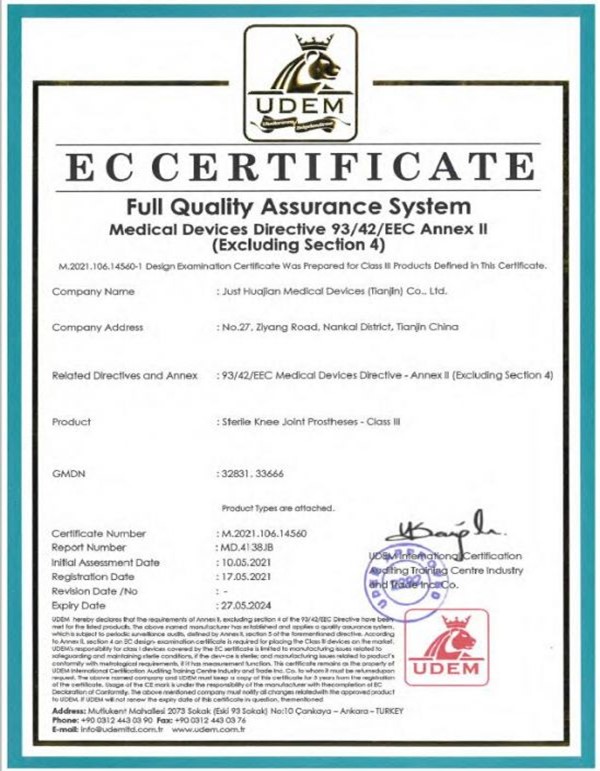

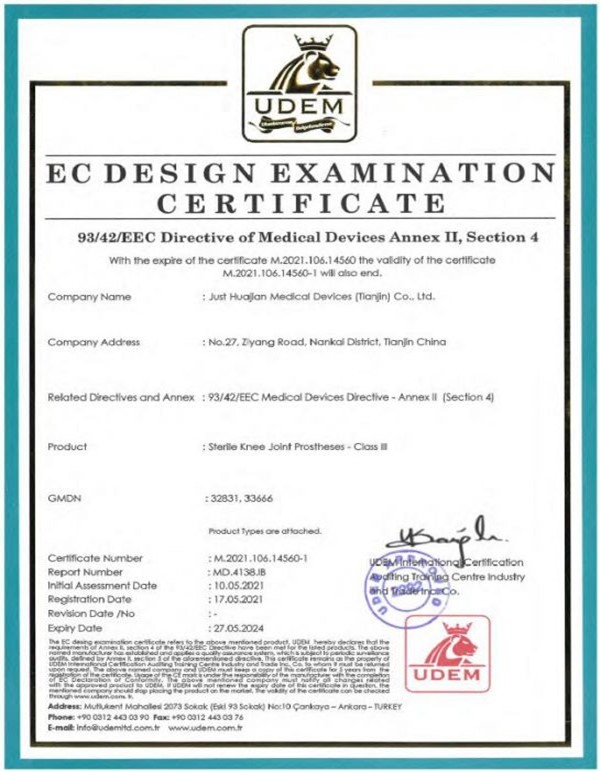

JUST has always insisted on taking the road of professional development since it was established, and "safety, effectiveness and convenience" are the requirements of all products and services. At the same time, JUST MEDICAL covers 5 functional aspects including R&D, manufacturing, marketing, training and servicing